The unanimous jury verdict that has turned Donald Trump from an alleged sexual assaulter into a proven one may create political shockwaves if recent history is any guide. As numerous empirical studies have shown, the American public has come to view sexual assault as a form of abusing power that can disqualify a perpetrator from holding public office. Trump may suffer significant political damage from this new majoritarian understanding.

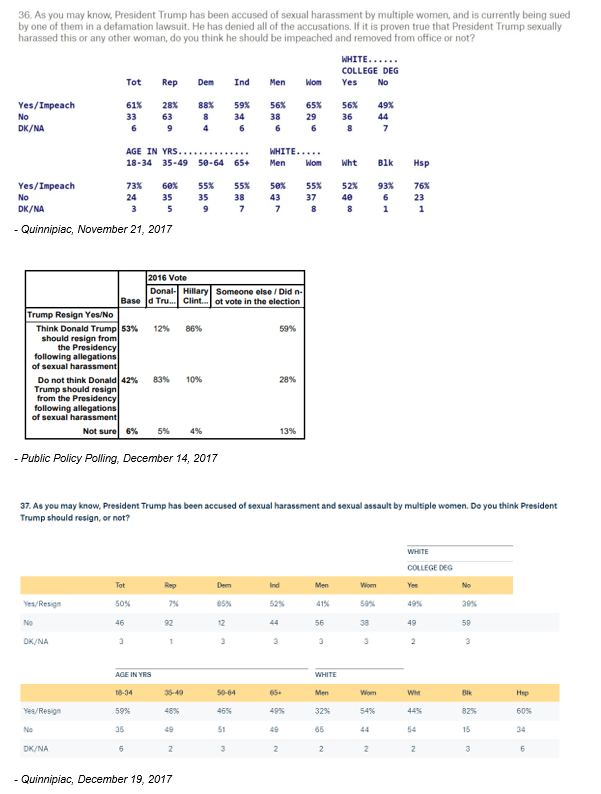

In November 2017, 61% of voters – including 56% of men and a nontrivial margin of white men (50-43) and white women (55-37) – said then-President Trump should be impeached and removed from office if he were proven to have engaged in “sexual harassment,” according to a Quinnipiac poll. That overall support – the eye popping number of 61% – was higher than any poll tracking public support for impeachment and removal from office for the scandalous conduct in Trump’s first and second impeachments (see Five Thirty-Eight’s complete collection of surveys for the first and second impeachment). What’s more, Quinnipiac asked only about sexual harassment not sexual assault in the case of Trump. The latter, which is also the core crime in the E. Jean Carroll verdict, would have presumably produced even greater levels of support for removal from office.

The Quinnipiac poll was not alone.

A December 2017 Public Policy Polling survey found 53% of voters thought Trump should resign because of the “allegations” of sexual harassment against him, and another Quinnipiac poll in December 2017 found that 50% of voters already thought Trump should resign because he had “been accused of sexual harassment and sexual assault by multiple women.” (See appendix below for the exact wording and results of each of these surveys.)

These results are no surprise when taken in context of recent social science studies. Rigorous empirical research shows that Americans generally consider sexual assault incompatible with serving in elected office or positions of public trust (see e.g., Savani and Collignon, 2023; Stark and Collignon, 2022; Masuoka, Grose and Junn, 2021; Craig and Cossette, 2020). A 2020 study in the journal Political Behavior found that “(1) a significant electoral penalty is likely to be assessed against politicians accused of sexual harassment; (2) the size of that penalty (in terms of lost votes and lower favorability) … is concentrated among co-partisans and, to a lesser extent, Independents.” That study, like many others, concerned “accusations” and “allegations” of misbehavior; the results are likely to be even more pronounced in the event of allegations being proven – especially in a court and especially by a unanimous verdict.

A number of caveats and qualifications are worth mentioning however as we consider the potential damage to Trump.

First, Republicans are less likely to electorally punish their own party candidates who face sexual harassment or sexual assault allegations, according to research findings. For Trump, that may mean less of a political cost in the primary election season than in the general. That said, Republican women are more likely than Republican men to do so. What’s more, some Republican primary voters may also look over the horizon at how voters in the general election will react to his having been proven to have committed sexual assault and accordingly wish to select a more competitive nominee for their party.

Second, while there are many cases of Republican and Democratic elected officials being compelled to resign or being electorally defeated following public allegations of sexual harassment or sexual assault, there are also counterexamples. One prominent counterexample is Trump himself in the 2016 campaign. What makes Trump’s victory even more complicated is that notable percentages of his supporters believed the allegations to be true, as William Saletan documented in 2017.

That being said, multiple factors seem to distinguish the allegations in Trump’s 2016 campaign from the Carroll verdict in 2024, and ultimately constitute bad news for the former president.

Factor one: There is a difference between a belief that something is true, and proven confirmation by a unanimous jury verdict that it is so. Indeed this was a jury verdict following a full-blown trial in which Trump’s attorneys had the opportunity to challenge the specific allegations. The Carroll case also involved jurors’ assessment not only of the evidence of her sexual assault, but also of two other witnesses who testified that Trump sexually assaulted them. In other words, the verdict is a reflection of the allegations of three women.

Factor two: The difference between sexual assault and sexual harassment, cuts against Trump. Several (but not all) of the surveys discussed by Saletan in 2017 asked respondents about allegations of “inappropriate behavior,” “unwanted sexual advances,” and “unwanted advances on different women.” The respondents were not asked about allegations of sexual assault, which presumably would have given them greater pause on whether to vote for Trump.

Factor three: There may be a difference in how voters assess Trump on these issues of sexual harrassment and sexual assault when comparing him to the alternative candidate for office – Hillary Clinton in the case of the 2016 election. Indeed, that may help explain why some Republicans were willing to vote him into office in 2016, but some of Trump’s 2016 voters supported his resigning from office on the basis of the mere allegation of sexual harassment (7% in one study, 12% in another) and a larger percentage of Republicans (28%) supported his impeachment and removal from office if allegations of sexual harassment were proven.

In deciding whether to vote for him in 2016, the alternative was a Hillary Clinton presidency. In the case of removal from office, the alternative was Mike Pence. If the alternative option helps explain the difference, it could spell a negative fate for Trump in the current presidential primary, where voters can choose a different Republican.

Factor four: A difference between 2016 and 2024 is the advent of the #MeToo movement following the women who stepped forward in 2017 to report on sexual assault by Harvey Weinstein. That movement has helped shape the public conscience over a short period of time, and demonstrated an ability to “limit motivated reasoning” and “temper partisan biases” when individuals’ assess politicians’ misconduct (Klar and McCoy, 2021).

The question of course is to what extent any of these voter preferences against the kind of behavior here at issue would translate into electoral outcomes. One need only look at voters’ overwhelming support for certain gun reforms — and the absence of any corresponding legislation — to understand the gap between voter preferences and political outcomes. There are many structural impediments to the expression of democratic choices in U.S. elections that go beyond the subject matter of this essay. It is notable, however, that a candidate’s having engaged in sexual assault has in many instances proven fatal to their holding public office.

* * *

With #MeToo translated into the political arena, many Americans have shown they are not willing to support a candidate for elected office who has committed sexual assault – with the understanding that such a severe abuse of power is simply disqualifying for holding a position of public trust. Time will tell if the E. Jean Carroll sexual assault verdict has the effect that a large majority of Americans said they wanted in 2017, namely, to deny the presidency to Trump if the allegation that he had engaged in such abominable conduct was proven. It now has been.

Cited Academic Works

Stephen C. Craig and Paulina S. Cossette. “Eye of the beholder: Partisanship, identity, and the politics of sexual harassment.” Political Behavior 44, no. 2 (2022): 749-777.

Samara Klar and Alexandra McCoy. “Partisan‐motivated evaluations of sexual misconduct and the mitigating role of the# MeToo movement.” American Journal of Political Science 65, no. 4 (2021): 777-789.

Natalie Masuoka, Christian Grose, and Jane Junn. “Sexual harassment and candidate evaluation: Gender and partisanship interact to affect voter responses to candidates accused of harassment.” Political Behavior (2021): 1-23.

Manu M. Savani and Sofia Collignon. “Values and candidate evaluation: How voters respond to allegations of sexual harassment.” Electoral Studies 83 (2023).

Stephanie Stark and Sofia Collignon. “Sexual Predators in Contest for Public Office: How the American Electorate Responds to News of Allegations of Candidates Committing Sexual Assault and Harassment.” Political Studies Review 20, no. 3 (2022): 329-352.

Jamillah B. Williams. “#MeToo and Public Officials: A post-election snapshot of allegations and consequences,” Georgetown University Law Center (2018).

Appendix: Polling Questions and Results